Why Is Performance Art a Mode of Generating Empathy and Social Acitvism

Abstract

Social-emotional learning (SEL) curricula are beingness increasingly implemented with young children; however, access to comprehensive programs can exist prohibitive for programs limited past finances, fourth dimension, or other factors. This article describes an exploratory instance study that investigates the utilise of creative activity in the direct promotion of empathy and indirect promotion of other social-emotional skills for early elementary children in an urban-based after-school setting. A novel curriculum, Creating Pity, which combines art engagement with explicit behavioral pedagogy, serves equally a promising artery for social-emotional skill development, and has particular importance for children from low-income households. Five children from racially minoritized backgrounds in grades kindergarten and first attended the Creating Compassion grouping intervention. Grouping-level data and individual data of direct behavior ratings suggested a modest increment in empathy development, responsible controlling, and cocky-direction skills and thereby provide a preliminary basis for further effectiveness investigation. Suggestions for hereafter research in this expanse are discussed in addition to social justice implications.

Research suggests that empathy, defined by Ishaq (2006) equally "the power to identify and express one's own emotions to read another'south emotions correctly and comprehensively" (p. S26), offers protective benefits to children (Lenzi et al., 2014; López et al., 2008). Researchers accept besides found that empathy tin can be taught (Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, 2016). As such, empathy is a cadre component of many social-emotional learning (SEL) curricula, which are gaining popularity globally and beyond the USA (Clayton, 2017; Cristóvão et al., 2017; Torrente et al., 2016). Although empathy-focused teaching can accept various forms, including role plays and games, lectures, and skill-building exercises (Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, 2016), fine art-based interventions, such as those researched by Darewych and Bowers (2017), correspond ane especially promising method for delivering empathy grooming to children. Given findings on links between empathy and creativity (Alligood, 1991; Carlozzi et al., 1995; Grant & Drupe, 2011) and the effectiveness of feel-based social skills training programs with children (January et al., 2011), a curriculum that combines these elements has the potential to be both engaging and constructive. Furthermore, in today's increasingly multicultural classrooms, arts activities offer English language language learners a valuable opportunity to actively participate and limited themselves more than fully (Brouillette, 2009). This commodity documents findings from an exploratory study using an arts-centered empathy curriculum implemented with kindergarten and starting time grade children in an urban later on-school setting.

Empathy Development

Empathy plays a role in children's psychosocial adjustment and serves equally a central prerequisite in prosocial behavior and interpersonal cooperation (Behrends et al., 2012; Castillo et al., 2013). Empathy makes way for understanding and connecting with others as well as for developing cocky-compassion, a trait that has been shown to defend against feet (Neff et al., 2007); has been linked to increased psychological well-beingness in adolescents and adults (Neff & McGehee, 2009); and protects against negative psychological wellness outcomes for gender non-befitting individuals (Keng & Liew, 2016).

Given neuroscientific scholarship on the interpersonally relevant processes involved in empathy, such as emotion sharing and regulation (Decety & Lamm, 2006), empathy provides an of import foundation for didactics children other social-emotional skills, such as human relationship skills (e.g., building healthy relationships) (CASEL, 2017). Researchers have identified connections betwixt young children'southward emotional awareness and their relational skills, which in turn offer children additional benefits, such equally increased classroom adjustment (Denham et al., 2015). Studies indicate that preschool children with greater emotional competence compared to their counterparts are more than likely to exhibit a prosocial orientation and behavior and are seen as more socially adept over time by their peers and teachers (Denham et al., 2012; Eggum et al., 2011; Ensor et al., 2011). Young children'southward relational skills and outcomes are of dandy consequence given findings that poor peer relationships in childhood are a risk factor for challenges afterward in life (Parker & Asher, 1987).

Previous studies in schools have shown that empathy serves equally a potent protective cistron against aggressive behavior in youth (Lenzi et al., 2014; López et al., 2008). Empathy not only serves equally a protective factor confronting engaging in aggressive beliefs but can also lessen the effects of existing risk factors, such equally peer deviance (Lenzi et al., 2014). These findings are especially meaningful for the provision of empathy-centered social-emotional health programs to children from low-income households, for whom psychosocial protective factors tend to erode over fourth dimension (Madsen et al., 2011). Given preliminary findings indicating that SEL programs may have long-lasting effects for children of a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds (Taylor et al., 2017), empathy-centered SEL may help to reinforce protective benefits of reducing aggressive behaviors in children from low-income households. This tin also aid stave off the deterioration of protective factors typically experienced by this population.

Empathy training has also been used to teach children to exist accepting of difference (Hollingsworth et al., 2003), and has been constitute to enhance the effects of prejudice-reduction programs for children (Beelmann & Heinemann, 2014). Some scholars have argued that empathy training offers long-term benefits to young participants' communities, as such training prepares children to become citizens who are attuned to self and others, and can relate peacefully across difference in a multicultural gild (Derman-Sparks, 1993; Taylor et al., 2017). Furthermore, researchers have speculated that empathy development serves as a fundamental precursor to building other central social-emotional abilities, including prosocial beliefs and interpersonal collaboration (Behrends et al., 2012; Castillo et al., 2013), cooperative learning (Denham et al., 2015), and accepting differences (Hollingsworth et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2017). The numerous benefits of empathy development amid children get in a vital skill for social-emotional didactics programs and an ideal area of focus for the nowadays exploratory written report.

Arts-Based Programs and Empathy

Studies suggest that arts-based programs may exist a peculiarly effective, engaging, and age-advisable approach for education children about empathy. Prior studies indicate that through engaging in creatively focused interventions (visual art and performance art), international middle and loftier school populations take fabricated pregnant gains in empathy (Castillo et al., 2013; Ishaq, 2006). Music, theater, visual arts, and poetry have all been used to teach empathy and emotional sensation to children and adolescents in the Us and the Great britain (Brown & Sax, 2013; Goldstein & Winner, 2012; Gorrell, 2000; Ishaq, 2006; Rabinowitch et al., 2013). More specifically, enquiry findings take shown that acting training increased empathy among elementary school-aged children (Goldstein & Winner, 2012); 8–eleven year sometime children had higher emotional empathy scores post-obit a musical grouping intervention (Rabinowitch et al., 2013); and arts-enrichment preschool children who took part in music, dance, and visual arts activities subsequently experienced greater emotion regulation (Brownish & Sax, 2013), which has been proposed equally a key component of empathy (Decety & Lamm, 2006).

Engaging in the arts facilitates and expands children's social, emotional, and academic learning (Kozol, 2005). Researchers have identified the close connection betwixt empathy and inventiveness (Carlozzi et al., 1995; Grant & Berry, 2011). More specifically, Carlozzi et al. (1995) establish positive relationships betwixt creative development and the ability to perceive melancholia messages and display sensitivity toward others' feelings. Therefore, they recommended that creative programming be incorporated in education curriculum delivery as a means to support children'due south empathy evolution.

Using inventiveness to scaffold empathy development allows children to go more enlightened of means to affect the lives of others and engage in perspective taking (Grant & Berry, 2011). Fine art activities that incorporate hands-on and group-based interactive approaches allow children to learn from their peers through creative expression (Davis, 2008), facilitate prosocial behaviors (Grant & Berry), and support identity formation and appreciation of cultural differences (Ishaq, 2006).

Rationale for Empathy-Focused Arts Programming for Early on Elementary-Aged Children

Although researchers indicated that pre-K and kindergarten children see larger gains from social skills programs than children in subsequently grades, and that such programs are more effective when they are experiential (January et al., 2011), few researchers have examined arts-based empathy programs with children younger than fourth grade. Thus, the present exploratory study was designed to fill this gap by developing and implementing an experiential arts curriculum aimed to engage early on elementary-aged children in artistic easily-on learning virtually empathy. Though the aforementioned studies examined the issue of arts programs on young participants' empathy development, few studies have investigated arts-based curricula that teach well-nigh empathy explicitly. Given that Brouillette (2009) suggested that the added pace of facilitated dialog and reflection about children's art "may nurture deeper levels of perception near the feelings and perspectives of others" (p. 22), we would wait the explicitly empathy-focused material in our arts curriculum to raise its benefits to participants and fill an existing gap in the literature. We hypothesized that easily-on artistic activities would permit young participants to interact and understand their peers through creative expression. When washed in a group setting, arts activities can help forge social bonds while supporting identity germination and cultural transmission (Ishaq, 2006).

The research team chose to apply visual fine art methods as the focus of the arts-based curriculum given that these approaches provide a forum for creating, sharing, and reinforcing positive cocky-concept and social skills (Trusty & Oliva, 1994). The utilise of visual arts production likewise offers low-cost options for the delivery of creative arts and empathy programming. The demand for low-cost SEL curricula is substantial (Wright et al., 2013). Children from low-income households are at a college adventure for experiencing mental wellness challenges compared to their peers who come from higher-income backgrounds (Wadsworth & Achenbach, 2005). Additionally, although the present study took place prior to the COVID-xix pandemic, nosotros recognize that the effects of the ongoing pandemic have further exacerbated the need for mental health supports and creative outlets for coping (Jefsen et al., 2020). Empathy-focused arts programming that uses visual arts methods can easily be administered in low- or nether-resourced schools or after-schoolhouse settings, even through remote means. Facilitating access to creative SEL programming is an absolute must, especially considering that SEL curricula tend to be costly, averaging approximately $6000 per program (Hunter et al., 2018).

Investigation into the development of empathy in immature children is a disquisitional footstep forward in the field of school psychology. In order to best address the needs of children at-risk, the intervention under investigation positions itself as a short-term, preventative early intervention program. Previous research has shown that SEL curricula for children can produce positive behavioral and cognitive change in as little as iv months (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2015).

Research Questions

Given the express nature of enquiry in this area with early on elementary-anile children, and the lack of conclusive evidence on the relationship betwixt empathy and its translation into other social-emotional skills on children younger than 13, nosotros aimed to examine the following research questions: (a) Is empathic creative educational activity constructive in promoting empathy in young children? (b) Is empathic creative instruction constructive in indirectly promoting other social-emotional skills in young children?

Typically, SEL programs are comprehensive, addressing interpersonal relationship building as merely one component of many other skill-building domains (CASEL, 2013). We hypothesized that a creatively focused curriculum, when aimed specifically at improving children'south relational skills, can be just equally constructive in developing empathy every bit traditional SEL curricula. Additionally, nosotros besides hypothesized that equally gains are made in children's empathy levels, gains will also be made in other areas of social-emotional development.

Methods

Participants

A group of five children amongst kindergarteners and first graders (ages 5 to 6 years old) was recruited to participate from an urban after-schoolhouse programme. All 5 children were eligible for free or reduced lunch. Three children were identified equally female and two were identified every bit male co-ordinate to the afterward-school's program records. All participants were children of immigrants who spoke languages other than English language at home. Racial and ethnic identities of group members included Asian-American, Middle Eastern, Latinx, Black, and Multiracial. The after-school programme serves roughly 200 children between the ages of five–eighteen in a geographic zone targeted by the urban city for resource mobilization efforts due to high rates of poverty and social gamble factors. The kindergarteners and first graders who attended the programme had the option of selecting afterward-school enrichment activities to participate in, including arts, science and technology, math, and writing programming.

Measures

To examine the outcome of the empathic artistic instruction on empathy, participants were administered the Index of Empathy for Children and Adolescents (IECA). The IECA is an interview consisting of 22 items that measures empathy based on private reactions to everyday situations. The IECA was administered by group leaders both earlier and after intervention. Use of the IECA has been validated in early unproblematic samples also as for other populations through adolescence (Bryant, 1982). Additionally, the IECA has shown invariance beyond gender, making it a useful tool for measuring empathy expression in chief school children (Lucas-Molina et al., 2016). All 22 items on the IECA are scored dichotomously (e.thou., "yes" or "no") and include reverse-scored items. A composite score ranging from 0 (lowest possible empathy score) to 1 (highest possible empathy score) is created based on the boilerplate of response values for all questions (Bryant, 1982). The IECA has reliability reported to range from 0.52 to 0.76 (de Wied et al., 2007).

In improver, the direct beliefs rating (DBR) was employed equally an assessment to measure both empathy and other social-emotional skill acquisition. The DBR consists of brief evaluative ratings of children'southward social-emotional and behavior functioning through directly observations of operationally defined behaviors (Christ et al., 2009). The DBR was used by group leaders to assess child levels of social-emotional skill behavior while participating in the small group intervention. Employing the DBR inside an intervention parcel has demonstrated hope in increasing appropriate child beliefs in the classroom and can be used with children in grades kindergarten and upwardly (Chafouleas et al., 2012). Each form contains a calibration with eleven segments (numbered as a percentage of time from 0 to 100 at x-point intervals) that is anchored with three qualitative descriptors of (i) 0% of the time (non at all), (ii) 50% of the time (some), and (iii) 100% of the time (ever), as well every bit examples of behavior (e.one thousand., listening, showing concern for others, cooperating and communicating with grouping members, correctly identifying and reacting appropriately to others' emotions, resisting inappropriate social pressure, etc. [Chafouleas et al., 2012; Kilgus et al., 2014]). In the case of the present exploratory study, the behaviors used on the DBR were measured in accordance with the 2017 Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning: Social Awareness and Relationship Skills (CASEL) framework definitions and included: cocky-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, and empathic behavior.

Procedures

Recruitment

Parents/caretakers and children were informed of the relational skill-building intervention via a flyer. The only tangible reward to children for participation was the provision of basic arts supplies at the conclusion of the program. The child group was filled on a first-come, get-go-served basis. Given the young age of the children and focus on social-emotional skill delivery, the inquiry squad capped enrollment at five children and closed recruitment. Due to repeated absences, i child's data were discarded (absent for three of five intervention sessions).

Consent

The research team provided a consent grade in English language to parents/caretakers who expressed involvement in the Creating Compassion programming. The consent form provided information about the different activities children would appoint in and explained that participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time without event. The parents/caretakers were required to review and sign the consent class in order to enroll their kid in the programme. Prior to submitting the written consent, parents/caretakers could ask questions to learn more about the program.

Curriculum

For the purposes of this study, the definition of empathy was adjusted from two cadre competencies developed by CASEL (CASEL, 2017). Empathy was operationalized as the ability to (a) have perspectives of others, (b) relate to others' experiences regardless of differing backgrounds or cultures, and to (c) create and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships with other group members. Examples of empathic behavior included (a) listening to others, (b) accurately reading others' emotions, (c) showing concern for other group members, (d) communicating with others, (e) cooperating with others, (f) resisting inappropriate social pressure, and (one thousand) seeking and offering help when needed.

The commencement four group sessions (baseline phase) consisted of engaging in simple arts projects and subsequent discussions most the art produced. Fine art projects lasted anywhere from fifteen to twenty min, followed by discussion of the art produced for the remaining time (45 min full per session). During the baseline phase, group discussion of produced art revolved around general observations also as narrations of individual work.

The intervention phase restructured the baseline give-and-take-based sessions and consisted of v sessions. One time weekly 45-min sessions were held during which the intervention was implemented. During the intervention phase, grouping leaders used explicit behavioral teaching, including roleplays, to teach each target behavior that focused on empathy evolution. These target behaviors included showing one is listening to others (eyes and ears on the speaker), reading others' emotions ("you seem sorry"), displaying concern for grouping members ("are y'all okay?"), communicating and cooperating (speaking calmly to reach a goal), considering others' perspectives (nodding while others are talking), and seeking and offering help. Two target behaviors were taught each session. Learned target behaviors were reinforced before introducing new skills in subsequent sessions. Children then engaged in fifteen–xx min of art activity and/or creation. Arts activities included painting, sculpting, dance, music, photography, collage, mixed media, and drawing. Following the art activeness and/or creation, children participated in discussions that were led by the group leader (a trained, doctoral-level researcher). A sample "Creating Compassion" intervention session is provided in Appendix A.

Prompts varied in art medium on a session-by-session basis. Discussions required children to present their work to the grouping and give a verbal description of this work every bit information technology related to the prompt and the session's target behaviors. These discussions aimed to target children's listening skills and interpersonal agreement and provide opportunities to practice the learned skills.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using a single-instance, AB study pattern (Kazdin, 2011). This design, which introduces treatment after baseline data are collected, was utilized to explore preliminary effectiveness of the intervention. Although an AB blueprint precludes the ability to determine experimental effects, it allows for the observation of progress monitoring in applied settings where adding a reversal-to-baseline phase would be unethical and permanent behavior change is sought (Kazdin, 2011). Furthermore, returning to baseline is unlikely to upshot in appreciable changes of beliefs when the targeted beliefs, in this instance empathy, is an acquired skill that cannot simply be unlearned.

Baseline data of social-emotional behaviors, including empathy, were collected prior to beginning the intervention. Interrater reliability was examined for the DBR to ensure ratings were consequent throughout the intervention. Whatever discrepancies during the first interrater reliability probe were discussed to clarify procedure for observational data drove.

IECA information was collected once for each child following a pre/mail service design. DBR data for empathy and social-emotional development were collected following an AB unmarried-case design for each child after each session according to the operationalized definition. After baseline data was gathered, the empathic arts intervention commenced with all group members.

The lead investigator carried out the intervention and collected information. Paper-based information (e.g., consent forms, data drove sheets) gathered for this project were marked with the participants' de-identified code numbers, stored in a locked file cabinet within the researcher'due south role, and could simply be accessed by members of the enquiry team. The listing of participant names and their corresponding participant codes were kept in a locked file separate from the newspaper-based data. De-identified paper-based data were then transcribed into a password-protected calculator database, only accessible to the chief investigator (PI). Participants typically took home any art they produced. Any fine art product that participants did not wish to keep was discarded at the after-schoolhouse program.

Research Team Training and Support Construction

An additional team member was recruited to concurrently lead sessions and collect data equally a secondary observer. Both team members had extensive prior experience working with children and some exposure to the use of arts-based counseling methods. While the PI had cognition of the IECA and feel with the DBR, both team members completed structured training to ensure authentic delivery of the study's measures.

This secondary observer was trained by the PI to ensure fidelity. Both the PI and secondary observer completed DBR-specific training through completion of an online module provided through the University of Connecticut (UConn, 2018). Crovello (2017) suggested that completion of the DBR's online training module can assist improve reliability of information between raters. Subsequently the online training module was completed by both raters, these raters and then practiced rating the DBR on recruited participants in a natural setting (during free play in an alternate activeness at the subsequently-school plan) before whatever sessions began until at least xc% agreement was reached across participants. One time this agreement check was completed, the secondary observer collected DBR ratings for all sessions, and the PI completed DBR ratings 22% of these sessions.

IECA training was minimal every bit the measure is straightforward, and both squad members had previous experience administering structured measures to participants. Throughout the report'south duration, the enquiry team met weekly to monitor progress. Both the PI and secondary observer prepared for each week's session past reviewing the lesson script and addressing any related questions. At the completion of the 9 weeks of study implementation, IECA data for participants were collected a second time. The data collected were scored by the PI and analyzed in conjunction with the research team.

Results

The goal of this exploratory report was to notice preliminary data for the effectiveness of the "Creating Compassion" curriculum in promoting children'due south social-emotional development, especially empathy. Both group-level and private-level information findings from this exploratory study are presented below.

Group Level

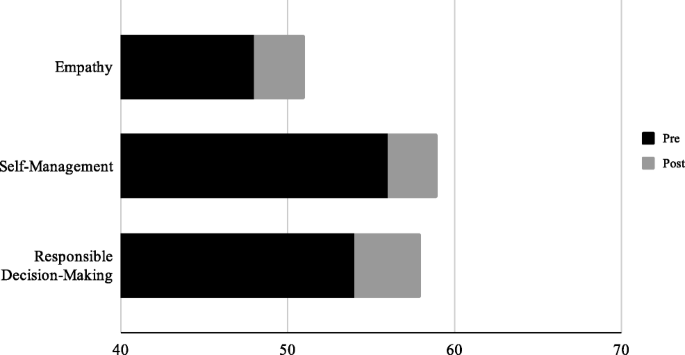

Mean IECA scores at baseline or pre-intervention (M = 10.5, SD = 3.eleven) did not significantly differ from postal service-intervention (G = eleven, SD = 2.94) IECA scores (p > .05). Baseline data obtained from the DBR showed kid mean pct of empathy increased from 48% (range = 40–53) of each session at baseline to 51% (range = forty–63) of each session post-obit intervention. In addition to empathic behavior increases, the percent of self-direction and responsible decision-making as well increased following intervention. Self-management increased from 56% (range = 47–63) to 59% (range = 53–63). Responsible decision-making increased from 54% (range = 47–63) to 58% (range = 53–65). A visual representation of group-level information is provided in Fig. ane.

Percent of time social-emotional skill behaviors observed by program phase across participants

Percentage of not-overlapping (PND) data is a proportion of information points in the treatment status that exceeds the extreme value in the baseline condition (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2001). Equally treatment is aiming to increase behaviors, the farthermost value would be the highest value during baseline condition (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2001). The percentage of non-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for empathic behavior was xl% (PND = 0.4, z = 0.9798, p = 0.3272, 90% CI = [− 0.272, 1]). The percentage of not-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for responsible decision-making was xx% (PND = 0.ii, z = 0.9798, p = 0.3272, 90% CI = [− 0.436, 0.836]). The percentage of non-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for self-awareness was 0% (PND = 0.0). The percentage of non-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for self-management was 0% (PND = 0.0). Scruggs and Mastropieri (1998) propose that PND scores above xc% represent very effective treatments, seventy–xc% are effective treatments, 50–70% are of questionable effectiveness, and below l% are ineffective treatments (Fig. 2).

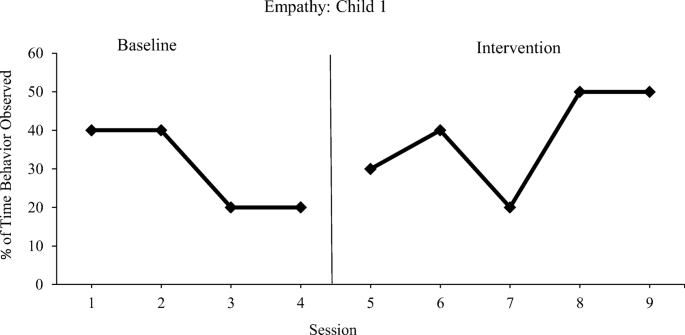

Percent of time empathy behavior observed past plan stage for child 1

Individual Level

Child 1

According to DBR data, kid 1 displayed a slight increase in empathy as a part of the intervention, with an average increase of rated empathy from 30% during baseline (SD = xi.55) to 38% during intervention (SD = 13.04). An increment of 20% to 30% empathic behavior rating after implementation could bespeak an immediacy effect of the intervention. The percentage of not-overlapping information between baseline and intervention phases for child one's empathic behavior was 40% (PND = 0.4, z = 0.9798, p = 0.3272, 90% CI = [− 0.272, 1]). The trend of the information also showed a decrease during baseline information, whereas data in the intervention phase showed a positive trend for child 1 (Fig. 3).

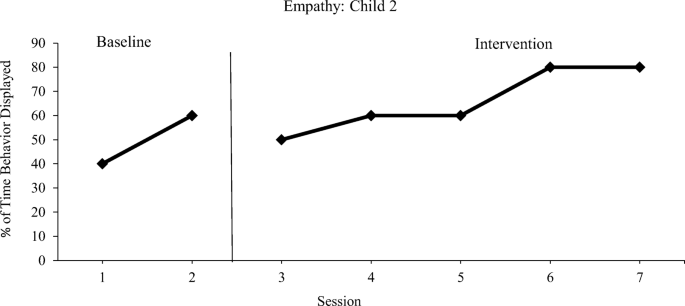

Pct of fourth dimension empathy behavior observed by programme phase for child 2

Child 2

Kid two's DBR data showed an increase in empathy from an average rating at baseline of 50% (SD = 14.14) to an average of 66% (SD = xiii.42) throughout the intervention phase. The pct of non-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for child 2's empathic behavior was xl% (PND = 0.four, z = 0.9798, p = 0.3272, 90% CI = [− 0.272, 1]). Although there was not an immediacy effect and data between phases overlap, the trend of the data showed positive increases in empathic beliefs (Fig. 4).

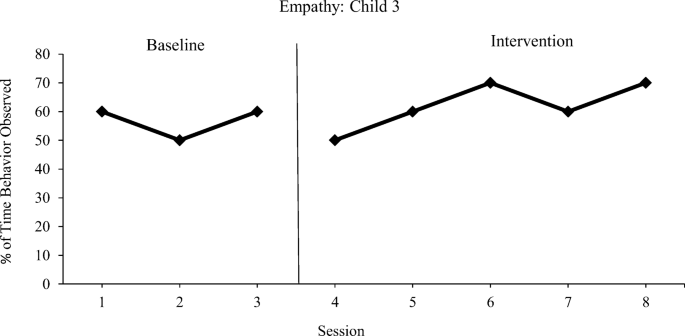

Percent of fourth dimension empathy behavior observed by plan phase for child 3

Child iii

The average level of child three's empathic behavior increased betwixt baseline and intervention from ratings of 56.7% (SD = five.77) to 62% (SD = eight.37) according to DBR data. There was no change in the tendency of baseline information, but the intervention data showed a positive upward trend. In addition, no immediacy effect betwixt phases was observed. The percentage of non-overlapping information between baseline and intervention phases for child iii's empathic behavior was 40% (PND = 0.4, z = 0.9798, p = 0.3272, 90% CI = [− 0.272, 1]). For child 3, there was still considerable overlap of information betwixt the baseline and intervention phases (Fig. 5).

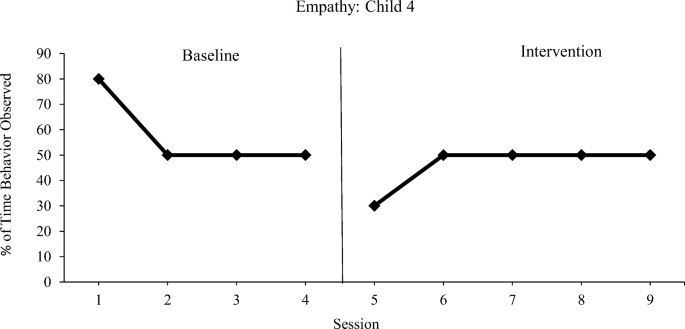

Per centum of time empathy behavior observed by program stage for kid iv

Child 4

Child four's DBR information indicated a decrease in empathy between baseline and intervention with a rating average of 57.5% (SD = 15.00) during baseline and 46% average rating (SD = 8.94) during intervention. These data too resemble a negative trend through baseline with a small change in the intervention trend. The percentage of non-overlapping data between baseline and intervention phases for kid 4'southward empathic beliefs was 0% (PND = 0.0). There was significant overlap between phases, and no immediacy consequence was observed.

Interobserver Agreement

In accord with best practice research procedures, at least 20% of behavioral observations should be reviewed by a second researcher in lodge to determine interobserver agreement (IOA) (Hott et al., 2015). Thus, the secondary observer scored participants on the DBR measurement tool independent of the PI for 22% of the observations across baseline and intervention periods. For the purposes of this report, if both observer's ratings were inside x% of each other in either management (plus or minus 10%), this was considered an understanding. Average IOA was calculated past dividing the total number of agreements between observers past the total number of opportunities for agreement beyond all sessions. Average IOA betwixt both raters for the DBR scale was 90.i% beyond the four behavioral categories.

Word

The modest increase in empathy documented in 3 of the 4 participants provides a preliminary ground for further exploration of arts-based empathy instruction with early elementary children. Social-emotional skills, including empathy, are essential to enhancing peer relationships, academic outcomes, and youth development outcomes overall (Taylor et al., 2017). This exploratory study adds to the research base that suggests explicit behavioral instruction may be a useful tool in social-emotional skill development. The Creating Compassion curriculum, aimed at improving children's relational skills, provides a footing for farther investigation into explicit behavioral teaching for SEL, specifically for empathy. Although percentage increases beyond target behavior demonstrations were pocket-size, over time, social-emotional skill development is expected to increment as children apply these skills in the existent world (CASEL, 2017; Melt et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2017).

More specifically, the research team aimed to explore whether empathic creative instruction (the Creating Compassion intervention) would promote the development of observable empathic behaviors. The results from the present exploratory study demonstrated a foundation for continued efficacy testing as at that place were modest increases in displays of empathic behavior for iii out of the four participants beyond nine sessions. Connected efficacy testing could include the provision of boosted sessions and then that participants have ample time to develop empathy skills. Even so, findings from the present exploratory study lend support to the possibility of building empathy skills through direct behavioral educational activity (Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, 2016). Moreover, the present report contributes to the school psychology literature by presenting a starting point for integrating arts-based empathy instruction in social-emotional interventions amid early on uncomplicated-aged children. Researchers have emphasized the demand for practitioners in the field to focus on delivering social skills interventions early on during babyhood to maximize opportunities for effectiveness, particularly for children from low-income households who may exist at risk for developing disciplinary challenges (January et al., 2011).

Additionally, results from this study may indicate that social-emotional skills do not develop in isolation. Rather, these skills accept an interactional consequence despite simply directly targeting i social-emotional skill—as gains are made in one skill domain, gains may likewise exist made in others. That is, the inquiry squad hypothesized that the Creating Compassion intervention would besides contribute to increasing social-emotional skill development more broadly every bit Darewych and Bowers (2017) found in their research. Findings from the present study provide preliminary support for this hypothesis insofar every bit participants demonstrated pocket-sized growth in SEL in the areas of cocky-management and responsible decision making from pre to postal service intervention with mean scores of directly behavior ratings showing a small increase. This finding is consistent with speculations that empathy development provides every bit a foundation to building other social-emotional competencies (Behrends et al., 2012; Castillo et al., 2013).

Limitations

Though rigor was ensured in information collection, conclusions of intervention effectiveness must exist fabricated with circumspection. Given that this was an exploratory study, our preliminary data prepare and AB pattern did not permit the states to brand stiff interpretations of the results. This design did not permit us to distinguish experimental effect from whatsoever possible confounds and could but be used to decide initial effectiveness. Thus, future research is needed to examine potential efficacy, such as through the use of multiple baseline design or mixed methods. The study'southward small sample (originally n = 5, with the eventual exclusion of ane participant's data due to inconsistent attendance) could besides exist interpreted as a limitation. Additionally, simply five intervention sessions were conducted due to the afterward-school program's scheduling needs. To better coincide with the academic calendar and allow for more than intervention sessions, future inquiry should allow considerable fourth dimension for recruitment before beginning the programme. Moreover, attempts were made unsuccessfully to secure caregiver interviews at the conclusion of the intervention, preventing researchers from gaining a qualitative perspective on plan effectiveness and behavior translation to other settings. Future research should target strengthening communication with participants' caregivers both earlier and during intervention and then that follow-up post intervention tin can be expected.

Future Enquiry

Time to come research should look to increase the sample size while besides introducing more rigorous inquiry methods, such as a multiple baseline design. Measurements of handling fidelity could be helpful, especially if this type of programme were to be implemented with larger sample sizes. Farther investigation into empathy development is warranted, and researchers should contain tools that ensure the intervention is implemented equally designed in gild to strengthen conclusions of effectiveness.

Implications

Despite limitations, findings from the nowadays study warrant further investigation into the outcomes of this detail curriculum and others similar it with young children. Arts-based empathy programs are promising in that they offer opportunities for schoolhouse psychologists to facilitate empathy development in young children in ways that are both hands-on and low-cost. The depression-cost nature of arts-based empathy-focused programs is probable to be attractive to school and afterwards-school programs that may otherwise be limited past finances, time, and other constraining factors. School psychologists tin capitalize on the inherent potential of, and opportunities presented past, arts-based empathy learning to promote SEL access for all children, especially those from lower-income households. These efforts can help further the social justice ideals fundamental to the responsibilities of all schoolhouse psychologists, just particularly for those interested in school-based disinterestedness leadership initiatives (Duma & Silverstein, 2014; NASP, 2010).

Arts-based empathy didactics has the potential to help young children develop of import interpersonal skills early on in life, while too exposing them to fine art, empowering them to engage in the creative process, and fostering emotional connections to their art and their peers. The deed of creating fine art and sharing it with others represents a powerful opportunity for the development of self-concept in children (Trusty & Oliva, 1994) and serves as a source of pride. Participation in the arts has been plant to enhance cocky-esteem and social skills among children from depression-income backgrounds (Mason & Chuang, 2001). Moreover, integrating arts-based activities in empathy training offers school psychologists opportunities to non just promote SEL development only likewise enhance school appointment, feelings of belonging, and overall schoolhouse climate (Catterall et al., 2012; Cratsley, 2017). Given findings on the protective benefits of empathy (Lenzi et al., 2014; López et al., 2008), in conjunction with results from the nowadays report, investigating empathy development in an urban, multicultural setting, specifically with children from low-income households, represents an important step forward in preventive and promotive efforts within the field of schoolhouse psychology.

Data Availability

Upon request via email, the first author (laura.morizio001@umb.edu) tin can provide any available de-identified data for reader review.

References

-

Alligood, K. R. (1991). Testing Rogers'south theory of accelerating alter: The relationships amid creativity, actualization, and empathy in persons eighteen to 92 years of historic period. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 13, 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394599101300106.

-

Beelmann, A., & Heinemann, K. S. (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent grooming programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2013.eleven.002.

-

Behrends, A., Müller, S., & Dziobek, I. (2012). Moving in and out of synchrony: A concept for a new intervention fostering empathy through interactional movement and dance. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.02.003.

-

Brouillette, L. (2009). How the arts assist children to create healthy social scripts: Exploring the perceptions of elementary teachers. Arts Education Policy Review, 111, sixteen–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910903228116.

-

Brown, Due east. D., & Sax, 1000. L. (2013). Arts enrichment and preschool emotions for low-income children at run a risk. Early Childhood Inquiry Quarterly, 28, 337–346. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.ecresq.2012.08.002.

-

Bryant, B. K. (1982). An index of empathy for children and adolescents. Child Development, 53, 413–425. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128984.

-

Carlozzi, A. F., Balderdash, G. S., Eells, One thousand. T., & Hurlburt, J. D. (1995). Empathy as related to creativity, dogmatism, and expressiveness. The Journal of Psychology, 129, 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1995.9914974.

-

Castillo, R., Salguero, J. G., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Balluerka, N. (2013). Furnishings of an emotional intelligence intervention on aggression and empathy among adolescents. Periodical of Adolescence, 36, 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.001.

-

Catterall, J. S., Dumais, S. A., & Hampden-Thompson, G. (2012). The arts and achievement in at-risk youth: findings from four longitudinal studies (rep. No. 55). https://world wide web.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Arts-At-Risk-Youth.pdf

-

Chafouleas, S. Thousand., Sanetti, Fifty. Thousand. H., Jaffery, R., & Fallon, L. Thousand. (2012). An evaluation of a classwide intervention package involving cocky-direction and a group contingency on classroom behavior of middle school students. Periodical of Behavioral Education, 21, 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-011-9135-eight.

-

Christ, T. J., Riley-Tillman, T., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2009). Foundation for the evolution and use of direct behavior rating (DBR) to assess and evaluate student beliefs. Cess for Effective Intervention, 34, 201–213. https://doi.org/x.1177/1534508409340390.

-

Clayton, Five. (2017). The psychological approach to educating kids. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/03/the-social-emotional-learning-issue/521220/

-

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2013). Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs: Preschool and Unproblematic School Edition [PDF]. Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/2013-casel-guide-1.pdf.

-

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2017). Core SEL Competencies Chicago, IL. http://www.casel.org/cadre-competencies

-

Cook, A. L., Hayden, L. A., & Denitzio, M. (2016). Literacy, personal development, and social development amidst Latina/o youth: Exploring the utilise of Latino literature and trip the light fantastic. Periodical of Kid and Adolescent Counseling, 2, 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2016.1172302.

-

Cratsley, L. (2017). Admission to arts pedagogy: An overlooked tool for social-emotional learning and positive school climate. https://all4ed.org/access-to-arts-educational activity-an-overlooked-tool-for-social-emotional-learning-and-positive-schoolhouse-climate/

-

Cristóvão, A. M., Candeias, A. A., & Verdasca, J. (2017). Social and emotional learning and bookish achievement in Portuguese schools: A bibliometric report. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1913. https://doi.org/ten.3389/fpsyg.2017.01913.

-

Crovello, N. J. (2017). The touch of online preparation on the reliability of directly behavior ratings. [doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut]. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1403

-

Darewych, O. H., & Bowers, N. R. (2017). Positive arts interventions: Creative clinical tools promoting psychological well-being. International Periodical of Art Therapy, 23, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1378241.

-

Davis, J. H. (2008). Why our schools need the arts. New York: Teachers College Printing.

-

Decety, J., & Lamm, C. (2006). Human being empathy through the lens of social neuroscience. The Scientific Globe Journal, 6, 1146–1163. https://doi.org/ten.1037/e633982013-133.

-

Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., Brown, C., Way, E., & Steed, J. (2015). "I know how yous feel": Preschoolers' emotion noesis contributes to early school success. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13, 252–262. https://doi.org/x.1177/1476718X13497354.

-

Denham, Due south. A., Bassett, H. H., Style, Due east., Mincic, Thou., Zinsser, K., & Graling, K. (2012). Preschoolers' emotion knowledge: Self-regulatory foundations, and predictions of early school success. Cognition and Emotion, 26, 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.602049.

-

Derman-Sparks, L. (1993). Empowering children to create a caring culture in a world of differences. Babyhood Education, 70, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.1993.10520994.

-

de Wied, K., Maas, C., van Goozen, S., Vermande, Grand., Engels, R., Meeus, Westward., Matthys, W., & Goudena, P. (2007). Bryant's empathy index: A closer test of its internal structure. European Journal of Psychological Cess, 23, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.23.2.99.

-

Duma, A., & Silverstein, L. B. (2014). A view into a decade of arts integration. Journal for Learning through the Arts, 10(1), 1–18 https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1050588.pdf.

-

Eggum, North. D., Eisenberg, N., Kao, K., Spinrad, T. L., Bolnick, R., Hofer, C., Kupfer, A. S., & Fabricius, W. Five. (2011). Emotion understanding, theory of mind, and prosocial orientation: Relations over time in early on babyhood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 4–16. https://doi.org/ten.1080/17439760.2010.536776.

-

Ensor, R., Spencer, D., & Hughes, C. (2011). 'Y'all feel sad?' Emotion understanding mediates effects of verbal ability and mother–kid mutuality on prosocial behaviors: Findings from 2 years to 4 years. Social Evolution, 20, 93–110. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00572.10.

-

Goldstein, T. R., & Winner, E. (2012). Enhancing empathy and theory of mind. Periodical of Cognition and Evolution, 13, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2011.573514.

-

Gorrell, N. (2000). Teaching empathy through ecphrastic poetry: Inbound a curriculum of peace. The English Journal, 89(five), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/822293.

-

Grant, A. M., & Drupe, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 73–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.59215085.

-

Hollingsworth, 50. A., Didelot, M. J., & Smith, J. O. (2003). Reach across tolerance: A framework for teaching children empathy and responsibleness. The Periodical of Humanistic Counseling, 42, 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-490x.2003.tb00002.ten.

-

Hott, B. L., Limberg, D., Ohrt, J. H., & Schmit, Grand. 1000. (2015). Reporting results of single-case studies. Journal of Counseling & Evolution, 93, 412–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12039.

-

Hunter, 50. J., Diperna, J. C., Hart, Due south. C., & Crowley, Chiliad. (2018). At what cost? Examining the cost effectiveness of a universal social–emotional learning plan. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(ane), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000232.

-

Ishaq, A. (2006). Essay: Evolution of children'south creativity to foster peace. The Lancet, 368, S26–S27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69915-7.

-

January, A. One thousand., Casey, R. J., & Paulson, D. (2011). A meta-analysis of classroom-wide interventions to build social skills: Do they work? School Psychology Review, 40, 242–256 https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ936452.

-

Jefsen, O. H., Rohde, C., Nørremark, B., & Østergaard, South. O. (2020). Editorial perspective: COVID-19 pandemic-related psychopathology in children and adolescents with mental disease. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Editorial Perspective. https://doi.org/ten.1111/jcpp.13292.

-

Kazdin, A. Due east. (2011). Single-instance inquiry designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Keng, S., & Liew, K. W. (2016). Trait mindfulness and cocky-pity as moderators of the association between gender nonconformity and psychological health. Mindfulness, viii, 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0639-0.

-

Kilgus, Southward. P., Riley-Tillman, T. C., Chafouleas, S. M., Christ, T. J., & Welsh, Yard. E. (2014). Direct behavior rating as a school-based behavior universal screener: Replication beyond sites. Journal of School Psychology, 52, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.11.002.

-

Kozol, J. (2005). The shame of the nation: The restoration of apartheid schooling in America. New York: Three Rivers Press.

-

Lenzi, M., Sharkey, J., Vieno, A., Mayworm, A., Dougherty, D., & Nylund-Gibson, K. (2014). Adolescent gang interest: The role of private, family unit, peer, and schoolhouse factors in a multilevel perspective. Aggressive Behavior, 41, 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21562.

-

López, E. E., Pérez, S. M., Ochoa, G. One thousand., & Ruiz, D. M. (2008). Adolescent assailment: Effects of gender and family and school environments. Journal of Boyhood, 31, 433–450. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.007.

-

Lucas-Molina, B., Pérez-Albéniz, A., Giménez-Dasí, G., & Martín-Seoane, G. (2016). Bryant'due south empathy index: Structure and measurement invariance across gender in a sample of primary school-aged children. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, nineteen, E44. https://doi.org/x.1017/sjp.2016.44.

-

Madsen, 1000. A., Hicks, G., & Thompson, H. (2011). Physical action and positive youth development: Impact of a school-based program. Journal of Schoolhouse Health, 81, 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00615.10.

-

Stonemason, M. J., & Chuang, Due south. (2001). Culturally-based after-school arts programming for low-income urban children: Adaptive and preventive effects. Journal of Primary Prevention, 22, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011088114.

-

National Association for School Psychologists (NASP). (2010). Model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services. https://www.nasponline.org/assets/Documents/Standards%20and%20Certification/Standards/2_PracticeModel.pdf

-

Neff, Yard. D., Kirkpatrick, Grand. L., & Rude, South. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Inquiry in Personality, 41, 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/e527772014-669.

-

Neff, G. D., & McGehee, P. (2009). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and immature adults. Cocky and Identity, ix, 225–240. https://doi.org/x.1080/15298860902979307.

-

Parker, J. G., & Asher, Due south. R. (1987). Peer relations and later on personal adjustment: Are low accepted children at gamble? Psychological Message, 102, 357–389. https://doi.org/ten.1037//0033-2909.102.three.357.

-

Rabinowitch, T. C., Cantankerous, I., & Burnard, P. (2013). Long-term musical grouping interaction has a positive influence on empathy in children. Psychology of Music, 41, 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735612440609.

-

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Summarizing single-subject research: Bug and applications. Behavior Modification, 22, 221–242. https://doi.org/ten.1177/01454455980223001.

-

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2001). How to summarize single-participant inquiry: Ideas and applications. Exceptionality, 9, 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex0904_5.

-

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Oberle, E., Lawlor, M. S., Abbott, D., Thomson, Thou., Oberlander, T. F., & Diamond, A. (2015). Enhancing cognitive and social–emotional evolution through a simple-to-administer mindfulness-based school plan for elementary school children: A randomized controlled trial. Developmental Psychology, 51, 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038454.

-

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88, 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864.

-

Teding van Berkhout, E., & Malouff, J. 1000. (2016). The efficacy of empathy grooming: A meta-assay of randomized controlled trials. Periodical of Counseling Psychology, 63, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000093.

-

Torrente, C., Alimchandani, A., & Aber, J. L. (2016). International perspectives on SEL. In Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice (pp. 566–587). New York: Guilford press.

-

Trusty, J., & Oliva, Yard. Chiliad. (1994). The effect of arts and music education on students' cocky-concept. Update: Applications of Enquiry in Music Education, 13, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/875512339401300105.

-

University of Connecticut (UConn). (2018). Direct behavior ratings (DBR) training. http://dbrtraining.education.uconn.edu/

-

Wadsworth, Thousand. E., & Achenbach, T. M. (2005). Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: Testing 2 mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 1146–1153. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.half dozen.1146.

-

Wright, R., Alaggia, R., & Krygsman, A. (2013). Five-year follow-upwardly study of the qualitative experiences of youth in an afterschool arts program in low-income communities. Journal of Social Service Inquiry, 40(ii), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2013.845130.

Funding

The inquiry was supported past the University of Massachusetts Boston'south Research Funding Grant in the corporeality of $500.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Laura J. Morizio. Methodology: Laura J. Morizio and Amy L. Cook. Implementation: Laura J. Morizio and Rebecca Troeger. Formal analysis and investigation: Laura J. Morizio, Amy L. Cook, Rebecca Troeger, and Anna Whitehouse. Writing—original typhoon: Laura J. Morizio, Amy Fifty. Melt, Rebecca Troeger, and Anna Whitehouse. Writing—review and editing: Laura J. Morizio, Amy Fifty. Cook. Funding conquering: Laura J. Morizio. Supervision: Amy 50. Cook.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they accept no conflict of interest.

Ideals Blessing

All procedures, materials, and related elements to the research were pre-approved and subsequently overseen by the University of Massachusetts Boston's Institutional Review lath.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants' parents.

Consent for Publication

Parents signed informed consent regarding publishing their children's data and any related findings.

Code Availability

Not applicative.

Additional data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix ane

Empathy lesson ane: lend an ear/ leap in their shoes

| Target empathy beliefs | What we'll call it | Verbal example | Nonverbal examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listens to others | Lend an ear | Repeating what was said, "uh-huh" | Centre contact, not speaking while others are |

| Actively considers others' perspectives | Bound in their shoes | "That would have fabricated me and then happy!" | Ten |

Lesson Time: 45 min total

Participant objectives:

-

Demonstrate explicitly what target behaviors look like and provide examples

-

Participate in an emotion-focused arts and crafts activity

-

Roleplay understanding others and emotion matching

-

Chronicle play activity back to discussion of empathy

Group goals:

-

Follow directions

-

Mind advisedly to peers

-

Participate in an activeness that promotes imagination

-

Piece of work together to come up upwards with different examples of empathy

-

Goals created by the group:

Opening (10 min):

Greet children back to the group. Communicate the importance of skilful listening and what that looks like (due east.g., ears open, eyes on speaker, mouths closed, easily upwards if you lot desire to speak). If good listening skills are observed, we will participate in a fabulous project!

Transition to empathy introduction. Suggested questions for brainstorming include:

- one.

"Has anyone ever heard the word 'empathy?'"

- 2.

"Whatever guesses as to what it might hateful?

Empathy definition: Empathy is the ability to empathise how someone else is feeling or to sympathise the situation they are in. It is the ability to "put yourself in someone else's shoes" and to understand the way a situation might make them feel.

Empathy role play between group leaders: "how was your day?"

-

Lend an ear examples: (a) repeating what was said (e.1000., "uh-huh"), (b) center contact, (c) non speaking over others

-

Jump in their shoes examples: (a) actively considering other perspectives, (b) echoing their emotional experience (e.g., "that would have made me so happy!")

Break off into groups (i group for each group leader) and practice sharing something skillful/bad that happened to you this calendar week. Group leaders will provide corrective feedback and appropriate praise.

Circle dorsum for discussion questions:

- one.

"Can you give me example of how you learned empathy today? We skilful two"

- 2.

Provide examples and role play situations with volunteers.

- three.

"Has anyone shown empathy to you? Tell me about information technology."

- 4.

"How does it experience when someone shows empathy to you?"

Fine art activity (x–15 min): happiest twenty-four hour period of my life

-

Glue sticks

-

Scissors

-

Construction paper

-

Markers

Ask participants if they are ready to brainstorm the activity. You tin can set them by maxim:

"Awesome answers, anybody! Now we are going to do some creative work that will help decorate the room. I desire anybody to remember what nosotros talked nearly on our word of empathy and what that means when nosotros think of our feelings. When you're prepare, discover some space where you lot tin can concentrate on what yous will be creating. We will exist working with art supplies, so get ready to have fun! Once you lot've found a space, enhance your manus and then I tin give you your supplies. I want you lot to draw a movie of the happiest day of your life! You tin can be in the movie if you desire, but but draw anything that you feel comfortable sharing with the group. If you lot terminate early on, y'all can inquire other people about their drawing."

Work should be done semi-collaboratively (meaning that children tin can share ideas while each producing an individual creation) and respect of each other's creations should be emphasized. Be sure to encourage children to think most the meaning of empathy while creating these. Assist children as needed.

Endmost (10 min):

Have children gather in circle and discuss what they have learned from the activity, how information technology relates to the empathy give-and-take, and how they tin can exercise this in school and at home. Ensure each child participates at least once in the word.

"Let's get around the group, one by one, and learn about the happiest days of our lives! I can go first."

Ask the group:

-

"How can we lend an ear?"

-

"Time to jump in their (the speaker's) shoes! What do you think that felt like?"

Close the word later on ensuring each child has an opportunity to participate. Example endmost prompts could include:

- ane.

"Has your idea of empathy changed since the beginning of this lesson?"

- 2.

"How tin can y'all show empathy at school?"

- 3.

"How can y'all bear witness empathy at home?"

End the session: Awesome work everyone! You lot made some gorgeous pictures! Feel complimentary to have your creation home to practise what we learned in group today!

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Morizio, 50.J., Cook, A.L., Troeger, R. et al. Creating Pity: Using Art for Empathy Learning with Urban Youth. Contemp Schoolhouse Psychol (2021). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s40688-020-00346-1

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s40688-020-00346-1

Keywords

- Social-emotional learning

- Empathy

- Artistic arts

- Social justice

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40688-020-00346-1

0 Response to "Why Is Performance Art a Mode of Generating Empathy and Social Acitvism"

Post a Comment